In 2017, armed with just enough soon-to-expire frequent flyer miles to snag a return ticket in business class between Cape Town and Ottawa via Addis Ababa, I fulfilled a long-standing desire to visit and photograph the rock-cut churches in Lalibela, a rural town in the Amhara Region of Ethiopia.

The country itself has long fascinated me. It stands as perhaps the only country in Africa never to have been colonised, although Italy did occupy it for several years around the Second World War, leaving behind a fondness for pasta and a thriving coffee culture. Indeed, most scholars agree Ethiopia is where coffee was first cultivated, and Ethiopian Harar coffee, reputed to be the world’s original java, is one of my favourite.

Ethiopia is home to the second oldest Christian religion in the world, the Ethiopian Tewahedo Orthodox Church, which predates the spread of Christianity to most of Europe. The church maintains that it possesses the Ark of the Convenant, the vessel Moses is believed to have constructed to hold the two stone tablets of the ten commandments. While the church refuses to divulge where it is keeping the Ark, it is undisputed that it does own what is believed to be the oldest surviving illustrated Christian manuscripts depicting large swaths of the Christian bible. (Sadly, this bible and other priceless artifacts were either stolen, secreted away for safekeeping, or destroyed during the two-year civil conflict that raged from 2020 to 2022 between the federal army and rebels in the northern Tigray region.)

In the 12th century, Gebre Mesqel Lalibela, a priest-king of the church, returned from a pilgrimage to Jerusalem and, believing that the recent Muslim capture of that city would mean the destruction of its temples, he had a series of 11 temples carved out of solid rock. It was part of what he believed was divine instruction to recreate Jerusalem; even the Tekeze River is known as the River Jordan where it runs through the town.

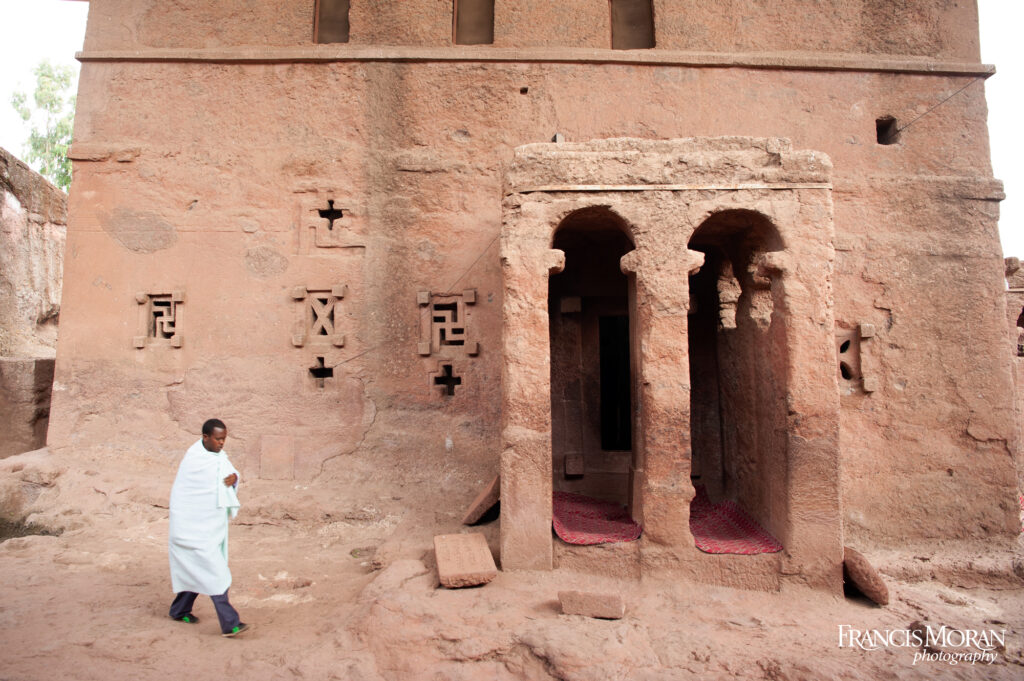

Each of the 11 churches was hand-carved out of solid rock during the 12th and 13th century. They are still in use today, with Lalibela ranking as the holiest city in Ethiopia and the site of massive annual pilgrimages. All 11 are designated as world heritage sites.

With a five-night layover in Addis, I booked a three-night hop up to Lalibela, a quick 90-minute flight to the western highlands of the country where a shuttle took me on the 90-minute drive to Lalibela. This is hill country, and that’s the closest to the town that enough flat land could be found for an airport. This is also arid country and, with seasonal rains expected within a month or two, the landscape was pockmarked with countless deep pits that cultivators had dug to catch and store the precious rains.

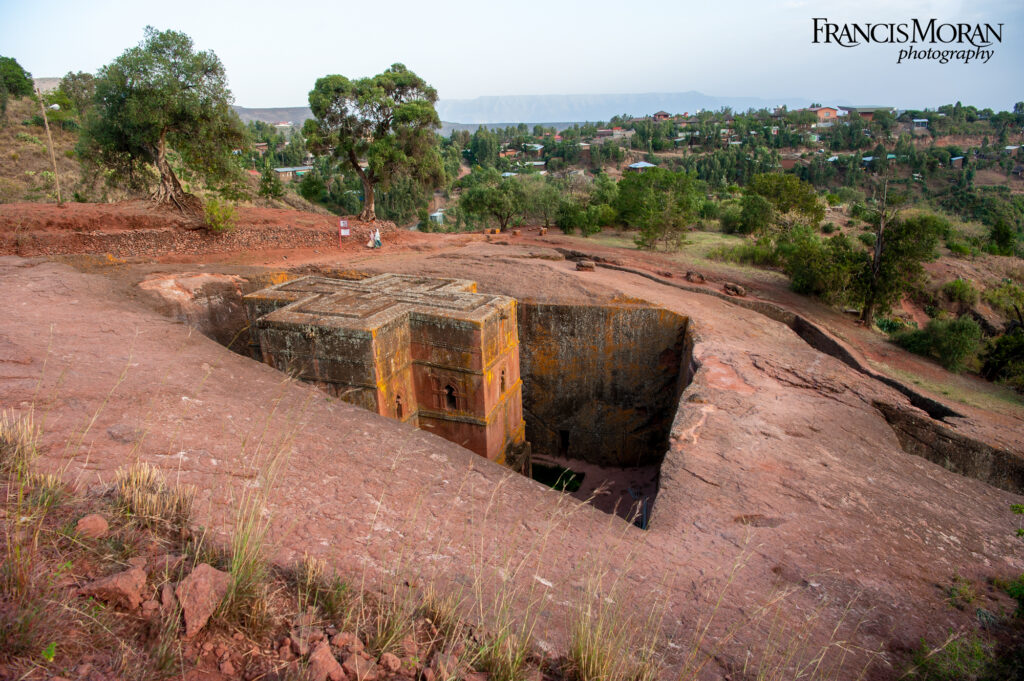

With a local guide, I made two trips to the churches, which are collected into two parts, with a third, the youngest and best preserved of them, standing alone. It is this church, Bete Giyorgis, the Church of St. George, which appears most often in posters about Lalibela and for good reason — it is the only one not covered by a protective roof to guard against further deterioration, and its commanding presence, standing in a deep hole in the solid rock out of which it was hewn, makes it incredibly photogenic.

All the churches are still in active use. Priests can be found in any of them on any given day, and the accoutrements of worship, such as carpets, drums and staffs that worshippers lean on during what I am sure are drawn-out liturgies, are strewn about. Between Christmas, called Genna in the Tewahedo calendar, and the feast of the Epiphany, or Timkat, tens of thousands of robed pilgrims descend on Lalibela, many of them finding shelter in the small caves and grottoes that dot the walls surrounding the churches. (My digs at Sora Lodge were far more comfortable.)

The marks of the hand tools used to carve the churches are plainly visible on their walls, and the whole thing inspires a level of disbelief that can be extinguished only by seeing them firsthand. Indeed, the first European to see the churches, Portuguese explorer Francisco Álvares, wrote, “I weary of writing more about these buildings, because it seems to me that I shall not be believed if I write more … I swear by God, in Whose power I am, that all I have written is the truth.”